How IT Can Aid Prison Reform

When North Carolina corrections officials introduced a new inmate health and safety observation system last year, they knew they had to get it right.

“There’s usually resistance because many of the procedures in prison are so critical,” says Bob Buckheit, a business application development specialist for the N.C. Department of Public Safety. “If this particular application had been a disaster, we would have poisoned the well. It was an important step to show that we could do this, and that it was reliable.”

Jails and prisons have earned an old-school reputation when it comes to technology, in part due to security concerns, and in part due to the reluctance of state and local governments to funnel scarce funds toward IT for correctional institutions.

“Jails and prisons are not profit makers,” says corrections consultant and former prison warden Daniel Vasquez. “The expenditures come from the general fund of the jurisdiction, and it takes years to get those approvals.”

But as inmate populations have swelled to include one out of every 100 Americans, jails and prisons are turning to technology to manage those populations and contain costs. In addition to inmate checking systems, some facilities have deployed video visitation systems and offender management systems that track charges, sentencing and medical issues, for example.

Kirk Vespestad, a spokesperson for the correctional technology company GTL, says some jails and prisons are even replacing wall phones with secure tablets that inmates can use not only to make calls, but also for education, entertainment and scheduling. “This is a trend that has only just begun to take shape,” he says.

Percentage of corrections officials who deem cost containment to be a significant or critical concern within their organization

SOURCE: Tribridge, “Challenges, Changes & Choices for Jails, Prisons and Corrections Facilities: New Requirements Demand New Technology,” 2014

Reducing Liability

In North Carolina, correctional officers use mobile devices to scan quick response codes when they perform inmate health and safety observations, then instantly enter information such as whether inmates are asleep or awake, and whether or not they have eaten their meals. Previously, officers walked rounds and then recorded their observations at their desks.

“We were using a paper system which we knew was not accurate,” Buckheit says, noting that officers relied on memory. Now, if an inmate lodges a charge against an officer for not providing proper care or delivering a meal or medicine, “the new system protects the officer, who can say, ‘I was there at that date, at that time.’ It also protects the inmate.”

Additionally, the system alerts prison officials of problems and eases policy enforcement across institutions, says agency CIO Bob Brinson. “If an inmate refuses six meals in a row, we want something to happen,” he says. “That’s hard to do statewide with a paper system. This new system makes things more uniform across a big state.”

The Mercer County Sheriff’s Office in Ohio deployed a similar solution last year. Deputies use a dedicated tool to conduct their checks, and the data is automatically downloaded to a server when the device is docked.

“It helps us know the checks were actually done,” says Sheriff Jeff Grey. “The only way they can do it is to actually be standing outside the cells. The supervisors can run a report and make sure the checks were done at the appropriate time.”

“It’s a liability issue,” Grey adds. “It protects the employee, so no one can say the employee lied. It also protects the county, because we have a record that would be pretty hard for anyone to alter.”

Cutting Costs

In addition to improving accountability, the inmate checking system streamlines operations. “The largest cost of running a jail is personnel,” Grey says. “We’re trying to find ways to streamline work so we don’t have to hire more employees.”

In San Francisco, which will soon pilot a body camera program for deputies, Sheriff Ross Mirkarimi expects the new technology to deliver this same sort of dual benefit. “We spend a great deal of time and resources investigating complaints, and I believe this will help upgrade our investigations while conserving resources,” he says.

Last year, the Milwaukee County (Wis.) Sheriff’s office rolled out a new video visitation system for prisoners. Such systems can free up staff that would otherwise be needed to escort and observe inmates for in-person visits. “It’s a zero-dollar cost to the taxpayer,” says Deputy Inspector Kevin Nyklewicz. The vendor, HomeWAV, charges users a per-minute fee to connect with inmates from their home computers. Visitors can also come to the jail to talk for free through an onsite video visitation system that CenturyLink supplied as part of its partnership with HomeWAV.

Nyklewicz says the home-based video visits reduce congestion at the jail and allow jail staff to monitor visits in real time. And despite the cost, the video visitation system appeals to many visitors. “When you have inclement weather or you have people who are up in age or not agile and able to move around, obviously the convenience of home is much better,” he says. The system also allows inmates to speak with their children at home, and even talk with people who live out of state.

Still, Nyklewicz says, “Some people prefer to come in to visit. I’ve had people tell me it helps them feel closer by being there.”

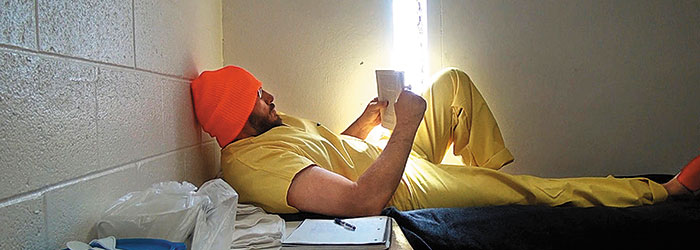

New Mexico Secretary of Corrections Gregg Marcantel, seen above, took the unusual step of placing himself in solitary confinement to experience it firsthand.

Solitary Struggle

New Mexico Secretary of Corrections Gregg Marcantel garnered headlines last year when he volunteered to spend 48 hours in a place where some of his inmates spend years: solitary confinement.

Also known as segregated housing, solitary confinement has become an increasingly controversial form of punishment, with critics charging that extended periods of isolation are tantamount to torture. Marcantel was already planning to reform the use of solitary, but he wanted to experience the confinement for himself as he evaluated its use.

“You really need to feel it,” Marcantel told a local news station. “You need to taste it. You need to smell it. You need to see it firsthand.”

The official struggled to pass the time alone, and told ABC News that his cell made him claustrophobic. “I felt like the cell was kind of squeezing down on me,” he said.

Marcantel remained firm in his belief that solitary confinement is required to protect his staff and other inmates from the most dangerous criminals. But he has already moved some prisoners out of the segregation unit, and has said it should be used only as a last resort. Many inmates who are housed in solitary confinement, Marcantel noted, will eventually be released from prison and will carry with them any psychological baggage that they pick up in solitary.

“We are sending them back to our neighborhoods worse than when they came,” Marcantel told ABC. “I can’t allow that.”